World Economic Situation And Prospects: October 2018 Briefing, No. 119

- Russian Federation commits to halving poverty by 2024

- China turns to pro-growth measures to mitigate the impact of the trade disputes

- Fiscal pressures creating significant policy challenges in Latin America

English: PDF (176 kb)

Global issues

Institutional change and the dynamics of inequality in Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States

Reducing inequality and accelerating growth of median incomes remain crucial challenges in the majority of countries across the world in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While a number of developing countries, predominantly commodity-exporters, made modest progress towards reducing inequality during the commodity price boom of the 2000s, these improvements were largely cyclical and subject to volatility in commodity markets. More lasting and significant improvements will require structural reforms. To this end, more countries are aligning their national development strategies with specific SDG targets, including SDG 1 (eradicating poverty) and SDG 10 (reducing inequalities). For example, China’s National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda contains a provision to “sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average”. The Russian Federation recently adopted a social development target to reduce poverty by half by 2024.

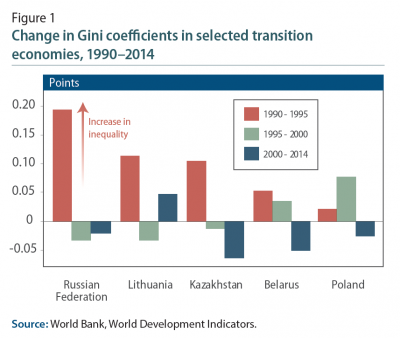

One group of countries where inequality generally remains high relative to levels observed thirty years ago are the former centrally planned economies of Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The profound institutional changes that took place in these countries since the late 1980s, including changes to the ownership structure of firms, price and wage liberalization, and increased openness to trade and capital flows, distinguishes them from most of the rest of the world. These changes have brought about a modern and competitive business environment, encouraged massive foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, supported technological upgrades of production processes, and spurred private entrepreneurship. However, these developments have also been accompanied by a marked increase in inequality in virtually all of these countries, both in terms of economic outcomes and opportunities (figure 1).

One group of countries where inequality generally remains high relative to levels observed thirty years ago are the former centrally planned economies of Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The profound institutional changes that took place in these countries since the late 1980s, including changes to the ownership structure of firms, price and wage liberalization, and increased openness to trade and capital flows, distinguishes them from most of the rest of the world. These changes have brought about a modern and competitive business environment, encouraged massive foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, supported technological upgrades of production processes, and spurred private entrepreneurship. However, these developments have also been accompanied by a marked increase in inequality in virtually all of these countries, both in terms of economic outcomes and opportunities (figure 1).

Precise measurements of inequality for the transition period are complicated by the large share of the informal economy and widespread self-employment, as well as the emergence of remittances as an important source of national income in several of the small economies. Available estimates of Gini coefficients show values close to 0.2 under central planning in the late 1980s, significantly lower than in most of the market economies. Within several years of eginning the economic transition, Gini coefficients in many cases exceeded 0.4. While significantly higher than in Western Europe, these levels remained lower than income inequality measures for many countries in Africa and Latin America. The dynamics of inequality varied depending on initial conditions, speed of transition and economic policies including provision of social safety buffers and minimum wages. Income inequality in the Russian Federation, in particular, rose sharply, as discussed further below.

Different factors contributed to the initial jump in Gini coefficients in the early 1990s. Perhaps the most important factor was the redistribution of wealth through the privatization of former publicly owned assets, including both productive assets and real estate. New types of income—business and rental—which were either non-existent or insignificant before the transition, became an important part of the national income. At the same time, the restructuring of enterprises by new owners involved massive layoffs in some cases. In most of the European transition countries, the industrial sector became dominated by European Union companies, aiming to modernize technology and integrate the sector into European production networks. This had a profound impact on labour markets, creating structural unemployment and a large stratum of people with low and unstable incomes. The shift from a predominantly manufacturing-oriented economy to an economy with a large share of services also had a significant impact on labour markets. Addressing structural unemployment remains a key policy challenge in many countries.

Another important source of growing income inequality was the introduction of wage and price flexibility, which was followed by episodes of high or hyperinflation. Although increasing wage differentials and rising inequality have been a widespread global phenomenon since the 1960s, former centrally planned economies saw a rapidly widening gap emerge in the 1990s between payments to high-skill and low-skill, productive and non-productive labour, especially in the rapidly expanding private sector. Wage disparities between different industries also emerged. Meanwhile, restructuring of the former State-owned enterprises shifted a large number of workers into less productive activities, often taking place in the informal economy.

In a number of countries, regional disparities also became pronounced, along with the emergence of “depressed regions”, where local economies had depended heavily on a single factory or were concentrated around a narrow range of industries that proved unable to withstand import competition. The scope to provide redistributive transfers to mitigate such disparities were limited due to weak tax collection or low corporate taxes and tax breaks intentionally offered to attract foreign investment.

Following the initial jump, income inequality in the former centrally planned economies generally stabilized in the early 2000s and has even receded slightly in some countries, while mean and median incomes, after the initial recession, have been steadily growing in real terms. Nonetheless, addressing elevated levels of inequality remains an important policy challenge. Policy instruments include direct fiscal measures aimed at redistribution through taxation and public spending, including cash transfers. Crucially, long-term improvements require addressing inequality of opportunity, by providing access to good quality education matching current labour market requirements, health care and necessary social services.

Developed economies

United States: A confluence of policy changes impact social and economic structure

Over the last two years, the Government of the United States has initiated a wide range of policy shifts in areas such as trade, taxation, immigration, and regulation. Some of these changes may have far-reaching and long-term implications for the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development in the United States. They also have the potential for significant global repercussions, and may impact international policy coordination efforts that address, for example, environmental policy or the challenge of large movements of refugees and migrants.

In addition to announcing the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement on climate change, there have been a number of broad policy moves towards lifting restrictions on oil and gas drilling in protected areas, easing commitments to reduce emissions, and encouraging expansion of fossil fuel sectors. The easing of environmental regulation has contributed to the sharp rebound in investment in mining exploration, shafts and wells, which more than doubled in the 18 months to June 2018. These policy shifts can be expected to delay the transition towards a greener energy mix in one of the world’s largest greenhouse

gas emitters.

Major changes in the level and structure of taxation are expected to stimulate economic growth in 2018 and 2019, but can also be expected to raise after-tax wage inequality, as corporation and households with the highest incomes reap higher levels of tax relief. Income inequality in the United States is already very high relative to other developed economies. Over the longer-term, lower levels of taxation will also raise the Government debt burden, which will eventually require fiscal adjustment either in the form of reduced provision of public services, such as healthcare, education and security, or a reversal of recent tax cuts.

The escalation of trade policy disputes and imposition of import tariffs have contributed to heightened uncertainty and tensions between the world’s largest trading partners. The tariffs have been met by retaliatory measures and a large number of disputes raised at the World Trade Organization. In addition to raising prices faced by households, these policy shifts may impact investment decisions and global production chains, and have the potential to reverse progress towards a universal multilateral trading system.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Inequality remains high in Russian Federation

Among the transition economies, the Russian Federation has recorded one of the highest levels of income inequality since the early 1990s. This can be attributed to the fast speed of transition involving the dismantling of the public ownership system, price liberalization followed by hyperinflation, the income tax system that applies a flat tax rate of 13 per cent regardless of income levels, and widespread wage arrears eroding incomes of those at the bottom of the income distribution. In the mid-1990s, the Gini coefficient for the Russian Federation approached a value of 0.5.

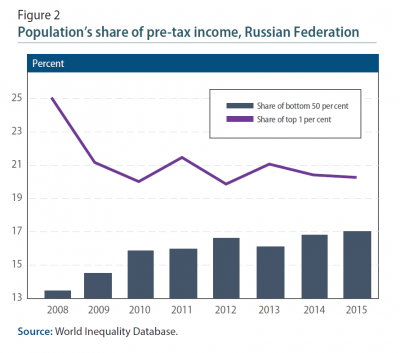

Following the commodity price boom of the 2000s, inequality in the country has declined modestly, reflecting strong commodity revenues, which allowed wage increases in the public sector in excess of productivity growth and stronger redistributive mechanisms. However, income inequality remains high by developed economy standards. According to the World Inequality Database, the share of the top 1 per cent of Russian income earners, while declining from 25 per cent in 2008 to 20 per cent in 2015, still exceeds the share of the bottom 50 per cent (figure 2). Over the same period, the share of gross national income captured by the bottom 50 per cent of income earners increased from 13.4 per cent to 17 per cent. Although Gini coefficients measured by Rosstat (the Federal State Statistics Service) and the World Bank differ, both series show a decline in inequality in 2015–2016. This suggests that the loss of revenue following the commodity price collapse and the impact of international sanctions have been felt most acutely by top income earners. This in part reflects lower returns on corporate bonds and other financial assets, as well as growing restrictions on the foreign activities of the business sector. On the other hand, incomes for the bottom cohort were preserved by partial indexation of public transfers and pensions, and the increase in minimum wage enacted in 2016. The recently adopted social development target to halve poverty by 2024 should contribute to further declines in inequality.

Following the commodity price boom of the 2000s, inequality in the country has declined modestly, reflecting strong commodity revenues, which allowed wage increases in the public sector in excess of productivity growth and stronger redistributive mechanisms. However, income inequality remains high by developed economy standards. According to the World Inequality Database, the share of the top 1 per cent of Russian income earners, while declining from 25 per cent in 2008 to 20 per cent in 2015, still exceeds the share of the bottom 50 per cent (figure 2). Over the same period, the share of gross national income captured by the bottom 50 per cent of income earners increased from 13.4 per cent to 17 per cent. Although Gini coefficients measured by Rosstat (the Federal State Statistics Service) and the World Bank differ, both series show a decline in inequality in 2015–2016. This suggests that the loss of revenue following the commodity price collapse and the impact of international sanctions have been felt most acutely by top income earners. This in part reflects lower returns on corporate bonds and other financial assets, as well as growing restrictions on the foreign activities of the business sector. On the other hand, incomes for the bottom cohort were preserved by partial indexation of public transfers and pensions, and the increase in minimum wage enacted in 2016. The recently adopted social development target to halve poverty by 2024 should contribute to further declines in inequality.

Developing economies

Africa: Strengthening social safety nets alongside fiscal reforms

In June, Egypt announced a substantial cut in fuel subsidies, which resulted in an immediate hike in the prices of fuel products and electricity. While the negative impact of this policy initiative on the welfare of the poor raises concerns, the Egyptian Government has also made clear its intention to strengthen social safety nets, including by scaling up the Takaful and Karama programme, a national cash transfer programme. This has the potential to offset much of the impact on lower income households.

Egypt’s recent policy changes reflect an ongoing trend in Africa, regarding the role of the government in addressing inequality and poverty, and enhancing social protection. Price control measures, to varying extents, were once widely applied in Africa. Subsidies were considered a key social protection policy tool to maintain stable prices of essential goods, particularly food and fuels. However, blanket subsidies are not effective tools to alleviate poverty and inequality compared to more targeted measures. First, subsidy expenditures tend to overgrow, as government is usually reluctant to raise the nominal consumer prices of subsidized goods even at a time of rapid inflation. Second, the bulk of blanket subsidies may accrue to the wealthier segment of the society rather than the poor. Moreover, the taxation structure in most developing countries allows for little recovery of subsidy transfers from those with higher incomes, as progressive income taxation tends to comprise a relatively small share of fiscal revenue.

In conjunction with fiscal reforms, more targeted social protection policy measures, including conditional and unconditional cash transfer (UCT) programmes, have increasingly been introduced in Africa since the mid-2000s. Recent evaluation studies of national UCT programmes in Africa revealed positive results not only for social protection but also economic production in terms of household-level multiplier effects and its spillovers to local economies. A detailed evaluation of the national UCT programmes in Zambia found a significant income multiplier effect through the increase in agricultural production and non-farm business activities. Although the appropriate design and implementation of UCT programmes is country-specific, taking into account the nature of poverty in the geographical and cultural contexts, the recent evaluation studies are encouraging for SDG 1 and 10.

East Asia: China announces measures to support growth amid escalating trade tensions

Trade tensions between China and the United States escalated further in September. The decision of the United States to impose new tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods was met with retaliatory measures by China, which announced tariffs on $60 billion worth of American goods. Amid heightened policy uncertainty, a protracted trade dispute between these two major countries poses a significant downside risk to the growth outlook of China as well as the East Asian economies. This reflects the region’s deep integration into global production networks, with China often at the centre of these networks.

Over the past few months, Chinese policymakers have announced a wide range of pro-growth measures, aimed at mitigating the effects of rising trade tensions on the economy. In September, the minimum threshold for personal income tax exemption was raised, in efforts to boost consumption growth. The Chinese Government also plans to introduce additional tax deductions for spending on childcare, parental elderly care and education.

On the financial front, restrictions on local government bond issuances were eased, to strengthen infrastructure investment. The central bank had also earlier reduced reserve requirement ratios on banks to stimulate credit growth. While likely to support growth in the short term, these measures may heighten the risk of a disorderly deleveraging process in the future.

Chinese policymakers also recently announced several strategies geared towards lifting the country’s medium-term growth and sustainable development prospects. These include the provision of financial incentives and the easing of business regulation in order to create a more conducive environment for entrepreneurship and innovation. Meanwhile, ongoing plans to attract more investment into the high technology sectors is also likely to lead to productivity and employment gains, while boosting competitiveness.

South Asia: Need for public policies geared towards strengthening international competitiveness

The short-term economic outlook for South Asia remains favourable, as economic activity across the region continues to be driven by private consumption, and in some cases, investment demand. However, in order to improve its medium-term growth prospects, the region needs to redouble public policy efforts towards strengthening its international competitiveness. Several indicators of global competitiveness show that South Asia is lagging on a number of fronts, such as attracting foreign investments, penetrating new markets, and diversifying and upgrading its export products. In addition, trade openness and regional integration remain limited.

South Asia’s efforts to improve technological progress, for example via research and development (R&D) investments, are also lacking in comparison to other developing regions. The region has an enormous untapped potential to strengthen its international competitiveness and to gain market share in exports. Some positive examples in the region include the software and business outsourcing sectors in India, the garment sector in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and the Sialkot manufacturing cluster in Pakistan.

Against this backdrop, South Asia needs to tackle these structural issues in a comprehensive manner. For example, policies to strengthen the business environment, with emphasis on industry-specific issues, can positively affect investment prospects. Trade policy changes and trade facilitation measures can significantly reduce the elevated trade costs across the region, facilitate access to foreign inputs for exporters, and strengthen participation in global value chains. Meanwhile, policies regarding foreign direct investments can encourage not only flows but also productive linkages, technology transfers and workforce training. For instance, recent policy changes in the automobile industry in India are expected to encourage foreign investments in the near term. In addition, public policies can take a more proactive stance to promote innovation, for example by uplifting public R&D interventions that can catalyse private R&D investments and by enhancing complementary factors such as infrastructure, labour skills and finance. Altogether, these public policies can encourage productivity gains across the region, a crucial aspect to improve potential growth and to make sustained progress towards sustainable development in the medium term.

Western Asia: Evolving role of the state in the major oil exporting countries

Along the agreed framework among the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), namely Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, VAT is being introduced in these countries. The introduction of VAT marks an historic event not only regarding fiscal revenue diversification but also regarding the social contract between the state and its citizens in respective countries. Economic diversification remains a primary policy goal for GCC countries, and this also requires transitioning away from the simple socioeconomic structure where the primary economic role of the state is to distribute its oil wealth to its citizens. This simple distributive social contract has gradually changed over the last three decades as the share of the non-oil sector in the economies expands, and more citizens become engaged in private sector jobs. However, the concept of direct taxation in the social contract is still new as the GCC citizens have mostly been tax-free until recently. The plunge in oil prices in 2014 pushed the GCC countries to embark on structural reforms in order to cope with both the short-run revenue loss and also to accelerate progress towards long-run economic diversification. The introduction of the VAT has created a valuable administrative infrastructure, which can act as a cornerstone for further economic and fiscal diversification in the GCC countries.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Fiscal pressures create significant policy challenges

Across Latin America, most governments have been undertaking fiscal adjustment efforts in recent years. While this has resulted in an improvement in primary fiscal balances since 2016, further consolidation is often needed, especially given prospects for rising global interest rates and risks of financial shocks. The situation is particularly challenging in Argentina, which entered a Standby-Agreement with the IMF in June. In a bid to restore market confidence, the Government has set up a new economic programme that aims to accelerate the pace of deficit reduction. The plan is to eliminate the primary fiscal deficit by 2019. For 2018, a primary deficit of 2.6 per cent of GDP is projected, down from 3.8 per cent of GDP in 2017. The planned austerity measures comprise both significant cuts to public expenditure, such as reducing the public wage bill and transfers to State-owned enterprises, and higher tax revenues, including a temporary tax on crop exports. While it is hoped that the new programme will put Argentina’s public debt on a firm downward trajectory and support a gradual disinflation process, it threatens to push the economy back into a prolonged recession. This could hit vulnerable populations hard—including through further rises in unemployment and underemployment—even as the plan puts in place safeguards to protect these groups.

Pressures for further fiscal consolidation also persist in other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, in particular those with high levels of public debt and large medium-term financing needs, such as Barbados, Brazil, Costa Rica and El Salvador. In Costa Rica, the fiscal deficit is projected to reach about 7 per cent of GDP in 2018. In response, the Government has proposed a fiscal reform plan, which, among other measures, aims to replace the current sales tax with a value-added tax on all goods and services, including basic and essential food items. In protest against the fiscal reforms, public workers have gone on a nationwide strike and demonstrations have erupted in different parts of the country.

Follow Us