Global Scans · Green & Sustainable Finance · Signal Scanner

Emerging Trends in Climate Finance Governance: The Weak Signal of AI-Enabled Transparency

Climate finance has surged to the forefront of global policy discussions following commitments at recent international climate summits, with countries pledging trillions toward adaptation and mitigation efforts by 2035. Amid these commitments, a subtle yet potentially disruptive development is emerging: the increasing role of artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced data governance in ensuring the transparency and accountability of climate finance flows. While much attention focuses on the scale of funding itself, the integration of AI-driven governance mechanisms signals a shift that could profoundly disrupt how funds are tracked, allocated, and audited across industries and borders.

What’s Changing?

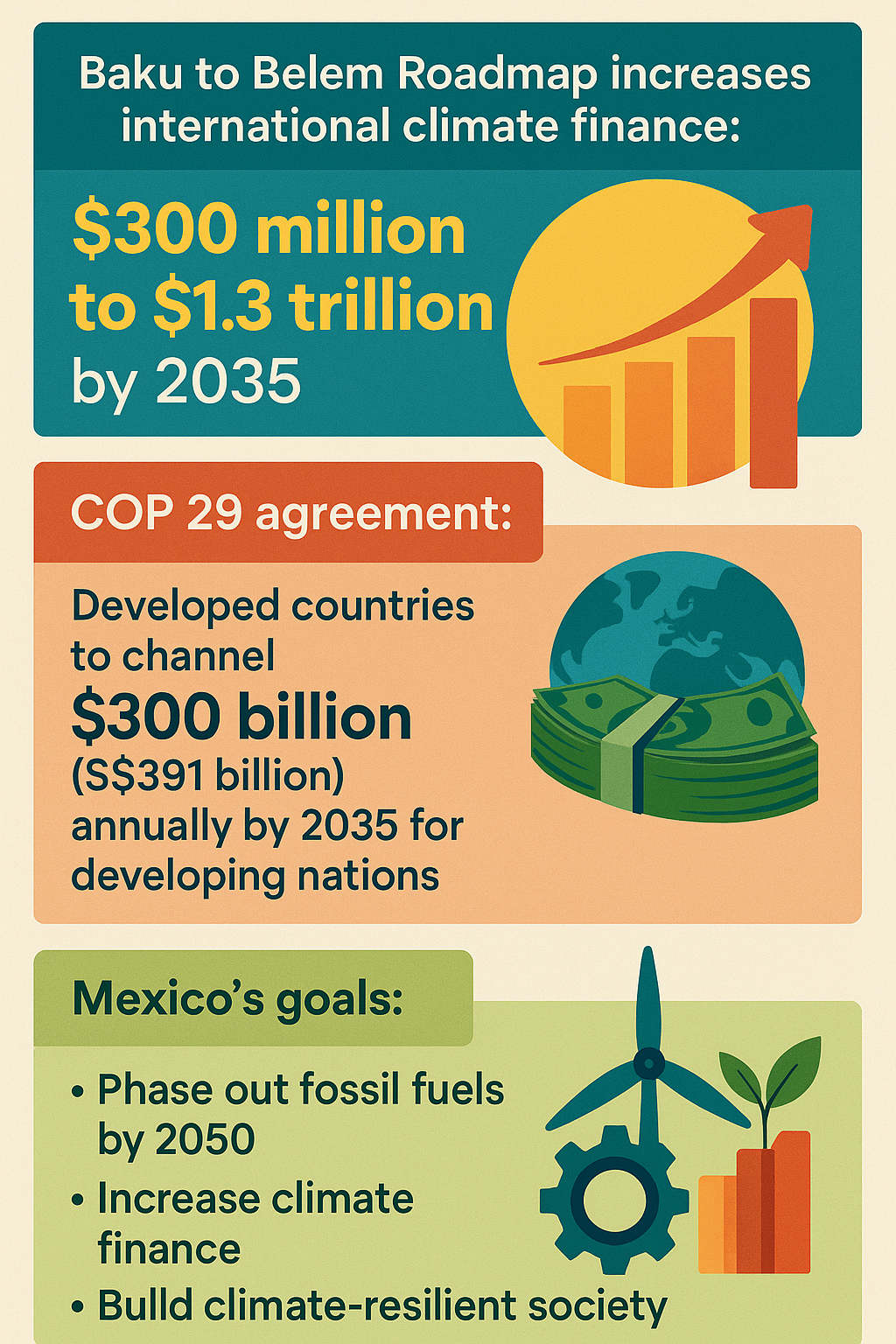

Recent climate summits, notably COP 29 and COP 30, have reiterated ambitious financing goals. Developed countries agreed to channel nearly US$300 billion annually to developing nations by 2035, aiming to scale up international climate finance to US$1.3 trillion (Source: El Pais, Astana Times). However, these immense volumes of funding will likely operate under increasing scrutiny amid concerns over corruption, mismanagement, and inefficient allocation.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have repeatedly emphasized the necessity for “credible governance” over both climate finance and AI investments (Source: Juan Cole). This marks a novel recognition that AI technologies will have a critical role beyond automation—specifically, in governing and verifying climate finance delivery and outcomes.

One significant emerging weak signal is that AI systems could enable real-time, automated transparency on how climate funds move through multilayered financial and political structures. Machine learning could identify anomalous transactions indicative of fraud or misallocation before funds are disbursed, while natural language processing might analyze local media or policy reports to verify project implementation and impact. Satellite data combined with AI-driven image recognition can corroborate environmental changes purportedly funded by climate finance.

Alongside this technical evolution, regulatory frameworks are evolving. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) planned 2028 ban on carbon credit trading among automakers (Source: Automotive World) exemplifies a broader global trend toward tightening carbon market regulations and compliance verification. Such governance tightening suggests that similar AI-enabled oversight tools could become mandatory or strongly incentivized in climate finance management across sectors ranging from automotive to agriculture.

Moreover, in countries like Mexico, which aims to phase out fossil fuels by 2050 and increase climate resilience (Source: Mexico News Daily), AI governance could support government agencies in monitoring progress, ensuring climate investments reach vulnerable populations and ecosystems effectively.

Why Is This Important?

The integration of AI into climate finance governance could disrupt traditional financial and auditing systems that rely heavily on human oversight, manual reporting, and opaque verification mechanisms. Improved transparency and verification increase stakeholder trust—including donors, recipient governments, NGOs, and the private sector—enhancing the legitimacy and efficiency of large-scale climate investments.

Business sectors involved in climate-related projects—renewable energy, infrastructure, carbon markets, agriculture—may face new demands to engage with AI-driven transparency platforms or reporting systems. Early adoption of such technologies could become a competitive advantage in securing international funding or carbon credits. Conversely, laggards might encounter capital access challenges or face reputational risks.

For governments and multilateral bodies, AI-enabled monitoring could reduce corruption risks and improve policy calibration by providing near real-time data on project performance and financial flows. This could foster more adaptive and responsive climate policies that are better aligned with local needs and emerging climate risks.

On a societal level, transparent climate finance governance empowered by AI may increase public accountability and civic engagement, bridging trust gaps between citizens and institutions. It could also reveal systemic inequities in how funds are distributed, enabling corrective action to prioritize marginalized communities disproportionately affected by climate change.

Implications

Organizations engaged in climate finance—whether governments, development banks, NGOs, or private investors—should anticipate a disruptive shift toward AI-supported transparency frameworks within the next decade. This shift creates several implications:

- Governance Structures Will Evolve: Climate finance governance will incorporate AI-enabled auditing and impact verification tools, pushing institutions to upgrade technological capacity and data policies.

- Risk Management Will Transform: Continuous AI-driven monitoring may become standard practice, allowing for proactive identification of compliance risks and early intervention to prevent fund diversion.

- Stakeholder Collaboration Will Intensify: Effective AI governance requires integrated data sharing between international bodies, governments, NGOs, and private entities, demanding new collaborative mechanisms and data standards.

- Regulatory Compliance Complexity Will Increase: Emerging standards or mandates for AI transparency tools across sectors may create compliance challenges, especially in jurisdictions with weaker digital infrastructure or governance capacity.

- Equity Considerations Must Be Central: AI tools must be designed and deployed to avoid reinforcing existing biases or excluding marginalized voices; equitable data governance frameworks will be critical.

Given the scale of climate finance commitments—from US$300 billion annually currently to a potential US$1.3 trillion by 2035 (Source: El Pais)—effective governance innovations could unlock more efficient deployment and greater impact of these funds, drastically influencing global climate outcomes.

Strategic actors should explore early pilot projects that integrate AI tools for transparency and impact assessment to identify best practices and technological limitations. Preparing governance and compliance teams for digital transformation will be essential. Cross-sectoral knowledge sharing on AI’s role in climate finance governance can also accelerate adoption and trust-building.

Questions

- How might AI technologies reshape accountability standards for climate finance in different political and regulatory environments?

- What risks could AI-driven transparency introduce in terms of data privacy, cybersecurity, or unintended systemic biases?

- How can multilayered stakeholders—donors, governments, NGOs, private sector—coordinate effectively around shared AI governance frameworks?

- Which industries beyond traditional finance and energy sectors are likely to be transformed by AI-enabled climate finance transparency mechanisms?

- What policy levers could governments or multilateral organizations deploy to encourage widespread adoption of AI governance in climate finance?

- How might small or vulnerable communities access or influence AI-based climate finance monitoring frameworks to ensure equitable outcomes?

Understanding and preparing for the rise of AI-enabled transparency in climate finance controls could provide governments, businesses, and civil society the tools necessary to maximize climate funding impact, reduce corruption risks, and accelerate progress toward a resilient, low-carbon future.

Keywords

climate finance; artificial intelligence; governance; transparency; corruption; carbon markets; climate adaptation; international development

Bibliography

- During COP 30, the UN Climate Change Conference held in Brazil in November, countries pledged to triple adaptation resources and set a target of mobilizing $1.3 trillion annually in climate finance by 2035. El Pais. https://english.elpais.com/climate/2025-12-05/the-destructive-storm-of-climate-change-is-looming-over-asia.html

- The IMF and World Bank reiterate at every opportunity that climate finance and AI investment need credible governance. Juan Cole. https://www.juancole.com/2025/11/vanishing-heating-corruption.html

- Phasing out fossil fuels by 2050, scaling up climate finance for people and the environment and implementing strategies to build a more climate-resilient society remain critical goals for Mexico. Mexico News Daily. https://mexiconewsdaily.com/opinion/sheinbaum-climate-change-commitments-mexico618916/

- The COP30 Effect: Experts weigh in on how climate talks affect people, jobs and nature in SE Asia. Strait Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/the-cop30-effect-experts-weigh-in-on-how-climate-talks-affect-people-jobs-and-nature-in-se-asia

- One of the outcomes from Baku was the Baku to Belem Roadmap to increase [international climate finance] from $300 million to $1.3 trillion for 2035. Astana Times. https://astanatimes.com/2025/07/exclusive-cop29-president-on-climate-goals-caspian-sea-deeper-trust-between-countries/

- NHTSA plans to eliminate carbon credit trading among manufacturers in 2028, ending a programme that allowed companies to purchase compliance credits from automakers like Rivian and Tesla with better compliance records. Automotive World. https://www.automotiveworld.com/news/trump-administration-proposes-fuel-economy-rollback/